“People have heard of La Specola,” the curator of the Museum of Portuguese Dermatology begins, surveying her kingdom of wax models of various venereal diseases. “But they’ve never heard of us.”

“People have heard of La Specola,” the curator of the Museum of Portuguese Dermatology begins, surveying her kingdom of wax models of various venereal diseases. “But they’ve never heard of us.”

I like her confidence. I like how she assumes, even though we’ve just met, that I know what La Specola is. She’s right, of course: the legendary Italian museum is a reference for anyone who’s ever looked into the history of making people out of wax. (The word that accurately describes the practice, however, is the very French “moulage”.)

Medical moulages, or models of diseased parts of the human body, were common educational aids in the 19th century. The perfect compromise between anatomical atlases and actual patients, these three-dimensional models were particularly useful to prepare students in the field of dermatology, as many diseases went unnoticed until they manifested (very, very dramatically) on the skin.

In order to create a moulage, a doctor would simply apply plaster to the affected part of a patient’s body and wait for it to dry. The hardened mold was then removed and filled with wax. The end result, a three-dimensional copy of the patient’s lesion, could then be painted to look as lifelike as possible. Voilà: a moulage!

We’ve since moved on from all that hassle, of course, but moulages are still very much around in medical museums all over Europe. The Museum of Portuguese Dermatology, in Lisbon, is home to a humble 254.

The collection occupies a single room in the once-grand Hospital de Santo António dos Capuchos. The building itself has seen better days, and I’ve heard there are plans to transfer the hospital elsewhere over the next couple of years. Even the clutter is moving out: up until recently, the basement looked like a medical historian’s wildest dream, but many of its contents have since been relocated to the shiny new Museum of Health just up the street.

For now, the moulages remain. I take my time with them, fully examining the craftsmanship and attention to detail expended in each one. The faces strike me as particularly lifelike, the features so natural it’s easy to ignore the circumstances in which they were captured. Just thinking about it ties my mind in knots: I’m looking at someone’s reaction to being covered in plaster in the name of medicine. How did they manage to look this peaceful? (I know I’d be kicking and screaming.)

For now, the moulages remain. I take my time with them, fully examining the craftsmanship and attention to detail expended in each one. The faces strike me as particularly lifelike, the features so natural it’s easy to ignore the circumstances in which they were captured. Just thinking about it ties my mind in knots: I’m looking at someone’s reaction to being covered in plaster in the name of medicine. How did they manage to look this peaceful? (I know I’d be kicking and screaming.)

The curator pulls a chair out for me as soon as I’m done touring the collection. She’s an historian, not a doctor, and she immediately apologizes for her inability to tell me more about the lesions on display–but would I like to hear about the long, terrifying reign of syphilis instead?

All I know about syphilis is that it is a bacterial infection transmitted mostly be sexual contact, so I sit down. Yes please. I want to know more, and I can’t imagine a better place to do it.

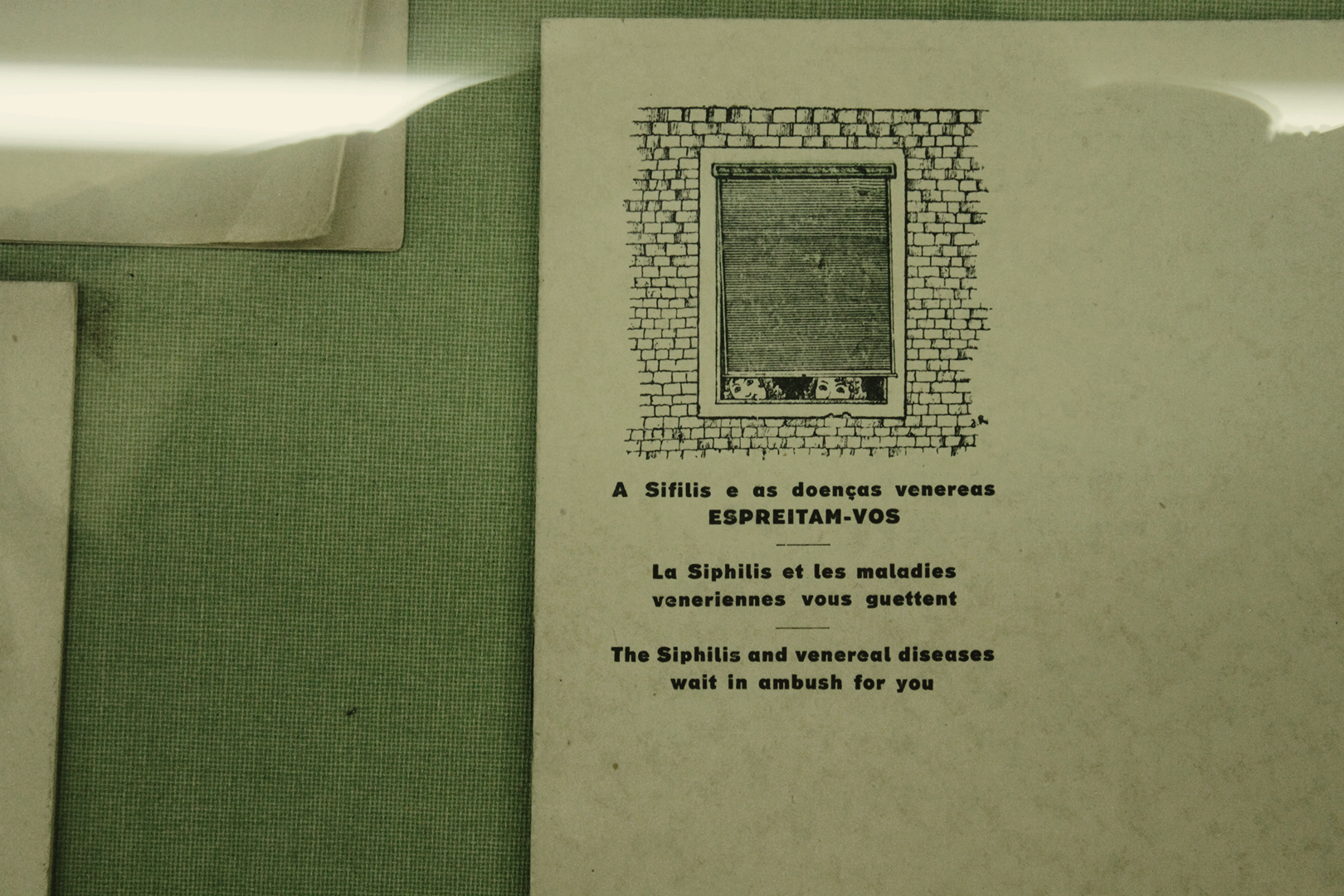

The first documented case of syphilis in Portugal dates back to 1496, the curator tells me, but the disease remained a formidable enemy up until the discovery of penicilin in the 20th century. It was during this later period, between the late 1800s and early 1900s, that the city of Lisbon doubled its efforts against the epidemic.

In 1897, Tomás de Melo Breyner, a 31-year-old noble turned physician, created the country’s first venereology (i.e. the branch of medicine concerned with venereal diseases, also known as STDs) practice at the now-defunct Hospital do Desterro. A compassionate man, Mello Breyner aimed to provide “the mangy, the pockmarked, and the harlots” with the kind of dignified and effective healthcare they’d been denied up until then. By 1906, he was leading a ward that cared exclusively for female sex workers. (Interestingly, the infirmary ward was named after Mary Magdalene, and the surgical ward after Mary of Egypt: two figures of Catholic iconography associated with prostitution.)

But sex workers weren’t the only sufferers of syphilis, of course–Mello Breyner provided ambulatory care to a wide range of patients. People of all ages, genders, and social classes came to be immortalized in his notebooks, as he penned down detailed accounts of their complaints and prescribed a variety of innovative therapies. Under his guidance, the Hospital do Desterro grew into a reference in the field of venereal disease, boasting multiple infirmaries that catered to every ailment imaginable in turn-of-the-century Lisbon. When Mello Breyner died, in 1933, his role as director of the venereology ward was passed on to Luis de Sá Penella–the man who would go on to popularize the practice of moulage in the hospitals of the Portuguese capital.

The majority of the 254 wax models that surround us, the curator tells me, were made under Sá Penella’s guidance in the aforementioned Hospital do Desterro, somewhere between the 1930s and 40s; the rest were commissioned right here, in the Hospital de Santo António dos Capuchos. (The entire collection of wax models can be seen online. The images are, needless to say, graphic.)

Today, at the dawn of the 21st century, Portugal no longer struggles with most of the conditions depicted in this collection. We have inherited this room of (horrifying) wonders, but we cannot, for the most part, imagine what it must have been like to live as patients lived. What a privilege that is, I tell the curator, and she nods gravely along.

Today, at the dawn of the 21st century, Portugal no longer struggles with most of the conditions depicted in this collection. We have inherited this room of (horrifying) wonders, but we cannot, for the most part, imagine what it must have been like to live as patients lived. What a privilege that is, I tell the curator, and she nods gravely along.

We part ways a couple of hours later, once we’ve spent the better part of the afternoon recounting the history of Lisbon through the lens of venereal disease. I know, even before I’ve fully left the Museum of Portuguese Dermatology, that I’ll be replaying this conversation in my head for years to come. I’ll be climbing Avenida da Liberdade in a few weeks or months, flanked by glossy haute couture shopfronts, and I’ll be thinking of how, just up the hill from here, the city’s hospitals used to be up in arms against an invisible foe that compromised and conquered every body it touched.

History is not all about men in uniforms declaring war on other men in different uniforms, turns out. Sometimes, it’s also about men in white coats declaring war on seemingly unbeatable ailments. It’s very, very rarely about the people whose bodies bear the brunt of said ailments, but places like the Museum of Portuguese Dermatology could help us change that. Here, at least, we can put a face to the anonymity that came with being a patient in the many hospital wards of early 20th century Lisbon.

The Museum of Portuguese Dermatology may be visited, every wednesday afternoon (information subject to change, confirm here), just off the cloisters in the Hospital de Santo António dos Capuchos. (Get your comfortable shoes on if you’re coming from Avenida da Liberdade: it’s quite a climb.)