Earlier this year, I got on a plane to London for a quick rendezvous with a philosopher. I was excited, people. I was so excited. I’d already built the set, angled the lights, and acted out the entire meeting in my mind: he’d receive me with that vaguely amused expression of his, hand on his cane, and I’d show my work by reciting some of his theories back to him while sneaking glances at the mementos scattered all over his little side table. I’d compliment his hat: “Cool hat, Jeremy!”

And he’d say nothing, because he’s dead. Obviously. Jeremy Bentham is very, very dead.

We set out to visit my good man Jeremy on our third day in the city. Bundled up in our overcoats (me) and fur-lined leather jackets (my co-traveler), we walked the mile between our hostel and University College London in amiable chatter, as I retold the exciting story of Jeremy Bentham’s preserved corpse for the hundredth time.

Philosopher, social reformer, general eccentric, Jeremy Bentham is mostly known for his panopticon, a very dystopian circular prison where inmates are under constant surveillance, and his utilitarianism, which asserts that the best course of action at any given time is the one that provides “the greatest happiness to the greatest number.” He’s also remembered, albeit less often, for his advocacy for gender equality, the decriminalization of homosexual acts, and the abolition of slavery and the death penalty.

And then there’s the whole… corpse thing. You see, before his death in 1832, Bentham left very specific instructions to a close friend, physician Thomas Southwood Smith, asking him to dissect and preserve his body. The Auto-Icon, as Bentham called this not-at-all weird art project, would be composed of his own skeleton, dressed in his own clothes and propped on his own chair, and his own mummified head, propped atop his spine so he could presumably continue to philosophize for all eternity.

Southwood Smith tried his best to fulfill the task, I’m sure, but good intentions be damned, he couldn’t exactly deliver on the mummification part. Bentham’s head was so unquestionably botched in the process that Southwood Smith left it between the Icon’s feet, choosing instead to commission a wax replica to place on his friend’s shoulders. By the time the Auto-Icon was donated to University College London, it was effectively bicephalous, but repeated student pranks resulted in the removal of the mummified head somewhere in the 1990s.

Fortunately for me, it was brought out of storage earlier this year and low cost flights are a thing that exists. Time to check “snap an ugly picture of Jeremy Bentham’s head” off my bucket list. (As for the body itself, I regret to say I never got to see it–but I did see the cabinet where they keep it, which counts for something. Feel free to head on over to my Instagram to read about this misstep.)

Respects paid to the father of utilitarianism, we crashed on a bench and replenished our blood sugar. We also scrolled down our social media feeds and quickly realized we were having the best time out of everyone we knew, since no one else seemed to be snacking a few feet away from a dead philosopher. With our self-esteem firmly secured, we stepped back out and continued our tour of the area around University College.

There are few things I love more than teeny tiny one-room museums. I love the proximity to the exhibits and I love the ingenuity it takes to do them justice in a small space and I love how the room never feels curated, even though it’s painstakingly so. To quote Paulo Cunha e Silva, a Portuguese art curator, “density is knowledge”, and nowhere is that more apparent than here, in the Grant Museum of Zoology.

Established as a teaching collection in 1828 by Robert Edmond Grant, a Scottish anatomist and zoologist whose influence extended to the work of Charles Darwin himself, this veritable room of wonders is so jam-packed with specimens you’d be hard-pressed to notice them all–or to pick a favorite.

Established as a teaching collection in 1828 by Robert Edmond Grant, a Scottish anatomist and zoologist whose influence extended to the work of Charles Darwin himself, this veritable room of wonders is so jam-packed with specimens you’d be hard-pressed to notice them all–or to pick a favorite.

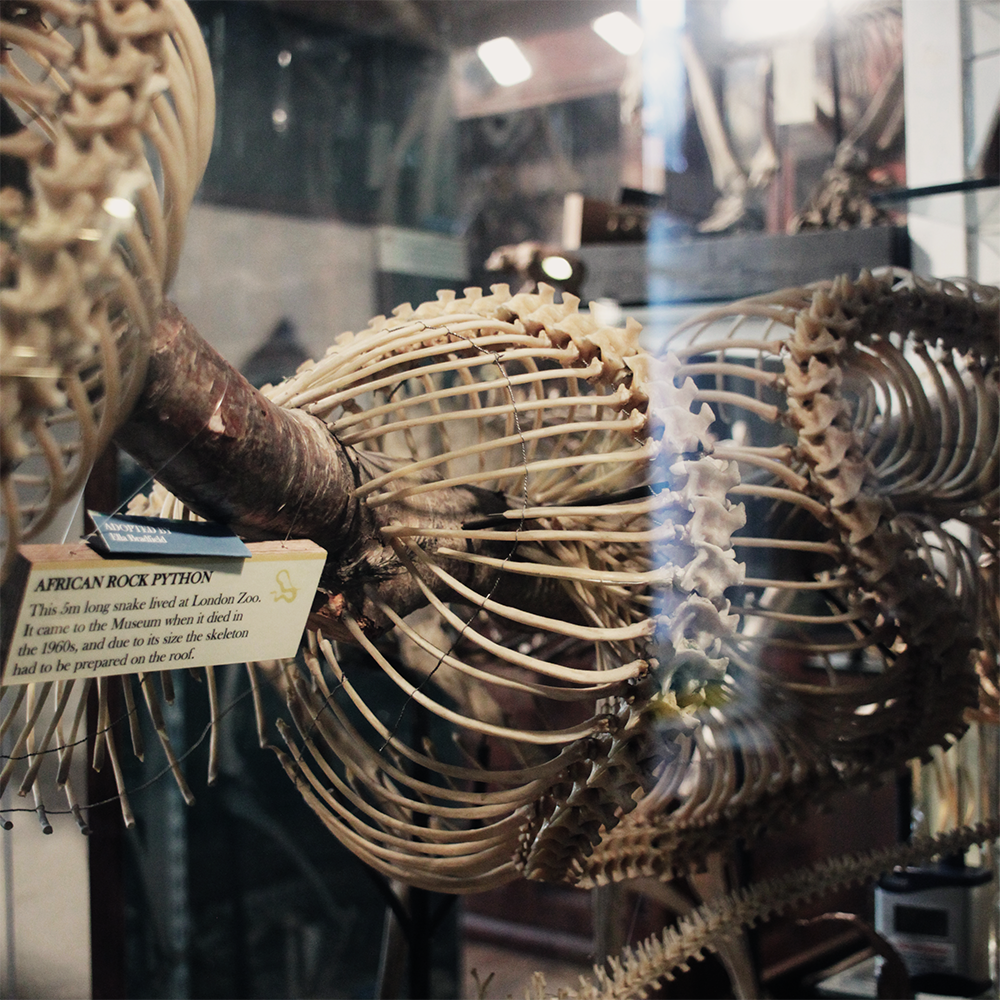

There’s the quagga skeleton, unique in the UK and matched only by six others in the whole wide world; there’s the set of dodo bones the museum didn’t even know existed until 2011, when it turned up in a drawer among bits and bobs of a crocodile; there’s the jar of moles with its own Twitter account; there’s a bisected pregnant cat and a pair of hilarious puffer fish and a snake skeleton coiled around a branch because there’s no room to display it elsewhere and there’s me, splaying my hands on the glass and staring silly at these treasures because this is my element, and I wouldn’t trade it for the world.

When I wrote about the natural history museum of Santiago de Compostela last year, I complimented its labeling system and overall user-friendliness, and I could say the same for the Grant, even though it presents itself in such a radically different way. It’s a thoroughly punk place, what with its mystery dodo and its tongue-in-cheek info cards and its dedication to its founder’s cause. It can’t be easy, being the last remaining university zoological museum in London, but the Grant seems undaunted; the day we visited, it was overrun with children poking gleefully at fossils and shark teeth. It felt pretty cozy, to be honest, and as the sun (the sun! in London! in February!) streamed through the large windows and filtered through the wet preps, I felt like I’d walked straight into a dream. An incredibly specific dream, yes, but a dream nonetheless.

I missed the Grant the moment I stepped out, but there was no time to mourn my new favorite place in the world. We were women on a mission, and by the time I pulled out my phone to double check our itinerary we’d already reached our second museum of the day: the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology.

Honestly, the Petrie is… humble-looking. Housed above a former stable, you could realistically walk past it without ever knowing you’d just snubbed one of the world’s leading collections of Egyptian material.

Honestly, the Petrie is… humble-looking. Housed above a former stable, you could realistically walk past it without ever knowing you’d just snubbed one of the world’s leading collections of Egyptian material.

The museum contains something like 80.000 artifacts, most of which belonged to Flinders Petrie, an English archaeologist who would go on to become UCL’s first ever professor of Egyptology in 1892. It’s worth mentioning, however, that the initial collection was donated by writer Amelia Edwards, who toured Egypt in the winter of 1873–1874 and developed a keen awareness of how tourism and development were quickly–and irreversibly–changing the landscape.

From the time of her voyage until her death in 1892, Edwards campaigned for and successfully funded three expeditions to Egypt, in order to salvage as many artifacts as possible before their inevitable destruction. (Which… seems a little counter intuitive to me if the intention is to preserve the Egyptian landscape, but was it ever? Was it really? Hmm. HMM.) Petrie joined the latter two expeditions, and Edwards respected his work and scientific mindset so much that she eventually made him, you guessed it, professor at UCL.

But back to the Petrie’s “humble” stacks. I’d climbed the stairs hoping to see the Roman period mummy portraits and few other things of note, so it’s fair to say I was wholly unprepared for the actual scope of the collection. The oldest dress in the world! More beaded jewelry than you shake a stick at! A pot burial! Glassware! Opium measures! Actual household objects!

My tween self would have loved the experience, but touring the Petrie as an adult I felt… detached, I think. I couldn’t engage with the collection in any meaningful way, even though everything I could have possibly wanted to see was well within reach. Maybe I was just academically unequipped to understand the displays, or maybe I’ve just grown out of my archaeology phase, the same way I’ve grown out of my ballerina/veterinarian/parapsychologist dreams. Ah well. People grow and change, and as our man Jeremy himself would have put it, “the rarest of all human qualities is consistency.”

There’s one thing I’m very consistently into though, and that is tea.

There’s one thing I’m very consistently into though, and that is tea.

So I thought we’d do that. My co-traveler and I would have afternoon tea, and we wouldn’t even be obnoxious about it. We wouldn’t mention Catarina de Bragança’s role in popularizing tea drinking among the English, and we would keep very quiet about the oldest tea plantation in Europe, which may be found in the Açores, Portugal. We would simply sit down, sip judgily from our fancy cups, nibble on our macarons, and relax.

We would do all this at the Wellcome Collection, a medical-slash-art museum that’s all about exploring “the connections between medicine, life and art”–or more precisely, at its second floor eatery, the Wellcome Kitchen. We would also, apparently, get so wrapped up in our tea-drinking personas that we would forget all about the actual museum. Until 30 minutes to closing time. As one does.

Up against the enormity of the task at hand, we had no choice but to split in the name of efficiency: my co-traveler took on the gynecological implements while I took on the paintings (including a 16th replica of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, arguably the pinnacle of human artistry), and we met by the Peruvian mummy and the fragment of Jeremy Bentham’s skin. Yes, that Jeremy. Again. We also ogled a printout of the human genome, daintily presented as a series of monochrome books, and stopped for a minute to discuss the pros and cons of trepanation.

The permanent exhibits at the Wellcome Collection are all over the place, yes, but so is medicine (and so is life, and so is art). Henry Wellcome, the pharmaceutical entrepreneur who collected most of these objects in the late 1800s and early 1900s, probably thought so too. He owned Napoleon’s toothbrush and Charles Darwin’s cane, and there seemed to be no grand distinction in his mind between these and the many, many thousand pieces of medical, scientific, and even domestic glassware he’d collected over the years. In a sense, this makes the Wellcome Collection the closest thing I’ve seen to a cabinet of curiosities, in that it provides a clear snapshot of the world as the owner saw it, strict criteria be damned.

Even the gift shop respected the loosely medical theme, stocking everything from beautifully bound books on medical illustration to “Blood Bath Shower Gel”. MEDICINE IS TOTALLY FUN, the Wellcome said, and I nodded along and bought fridge magnets, because I like it when museums understand they don’t have to be serious to be taken seriously.

Sure, there’s the public perception of museums as boring, stuffy old places where nothing ever happens and nothing ever changes, but I think otherwise: I think museums can only do so much on their own, and it’s up to me as a visitor to engage them in conversation. Sometimes I succeed, like I did with the Grant Museum of Zoology and the Wellcome Collection, and sometimes I fail, like I did with the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Either way, it’s always a learning experience.

I learned, for example, that I will not be visiting any more Egyptology museums in the near future. BAM.

Places in this post:

- Jeremy Bentham’s Auto-icon

- “What Does It Mean To Be Human? Curating Heads at UCL”, a temporary exhibition

- Grant Museum of Zoology

- Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

- Wellcome Collection (& Wellcome Kitchen)